The life-saving work of the New England Newborn Screening Program, operated by UMass Medical School, does not stop, even when severe weather strikes. Program staff showed unwavering dedication the day after a January blizzard, when they endured challenging road conditions and delayed public transportation to venture into work and then volunteer to collect blood samples from 25 hospitals in Eastern Massachusetts.

The combined efforts of the 52 staff members, including laboratory technologists, clinical reporters, faculty and workers from the front office and in data entry, helped save the life of Juliana Salvi. Had the lab waited for a snowed-in United Parcel Service (UPS) to deliver her blood spot days later, the now 9-week-old may have died.

“Our New England Newborn Screening Program is a team effort, and the most recent efforts of that team are to be celebrated and emulated,” said Dr. Roger Eaton, the program’s director.

Juliana was born with a rare genetic disorder known as galactosemia, which prevents the body from processing galactose, a sugar found in all types of milk and milk-based formulas. The last time a Massachusetts newborn was diagnosed after screening was more than two years ago.

The program receives and tests blood samples of babies across the Commonwealth and five other states and is staffed seven days a week. The blood samples are screened for 30 different rare genetic disorders (as mandated by each state’s department of public health) that can be life-threatening if not identified very early in life.

On Wednesday, Jan. 28, the day after a blizzard dumped more than 30 inches of snow in parts of Massachusetts, UPS announced that road conditions would prevent pickups of specimens from hospitals in Worcester and points east. UPS picks up blood specimens pricked from babies’ heels shortly after birth from hospitals across Massachusetts and delivers them overnight to the program headquarters in Jamaica Plain for testing.

Eaton asked for volunteers to visit hospitals near their homes and pick up specimens; the staff covered not only the affected area, but well beyond their homes. While an unsuspecting family brought Juliana home, her specimen happened to be in a batch that was picked up by lab technician Melody Rush, who got back to the lab in time for the specimen to be tested during the afternoon batch. “We all worked together to pick up these specimens,” Rush said. “It was a nice feeling knowing it made a difference in that case.”

There was a good likelihood that all specimens collected would have normal results, but the staff knows there is never a guarantee and went to work.

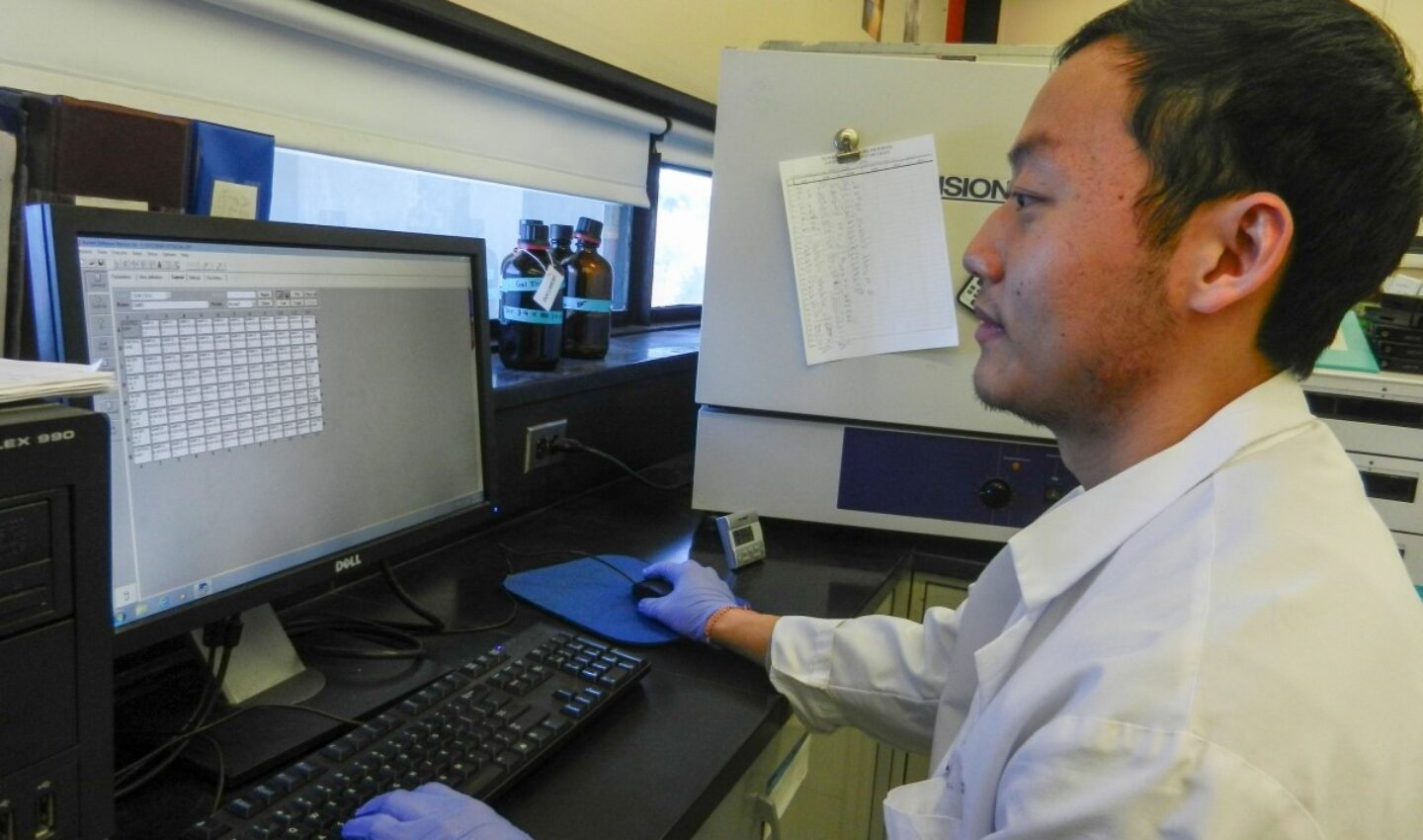

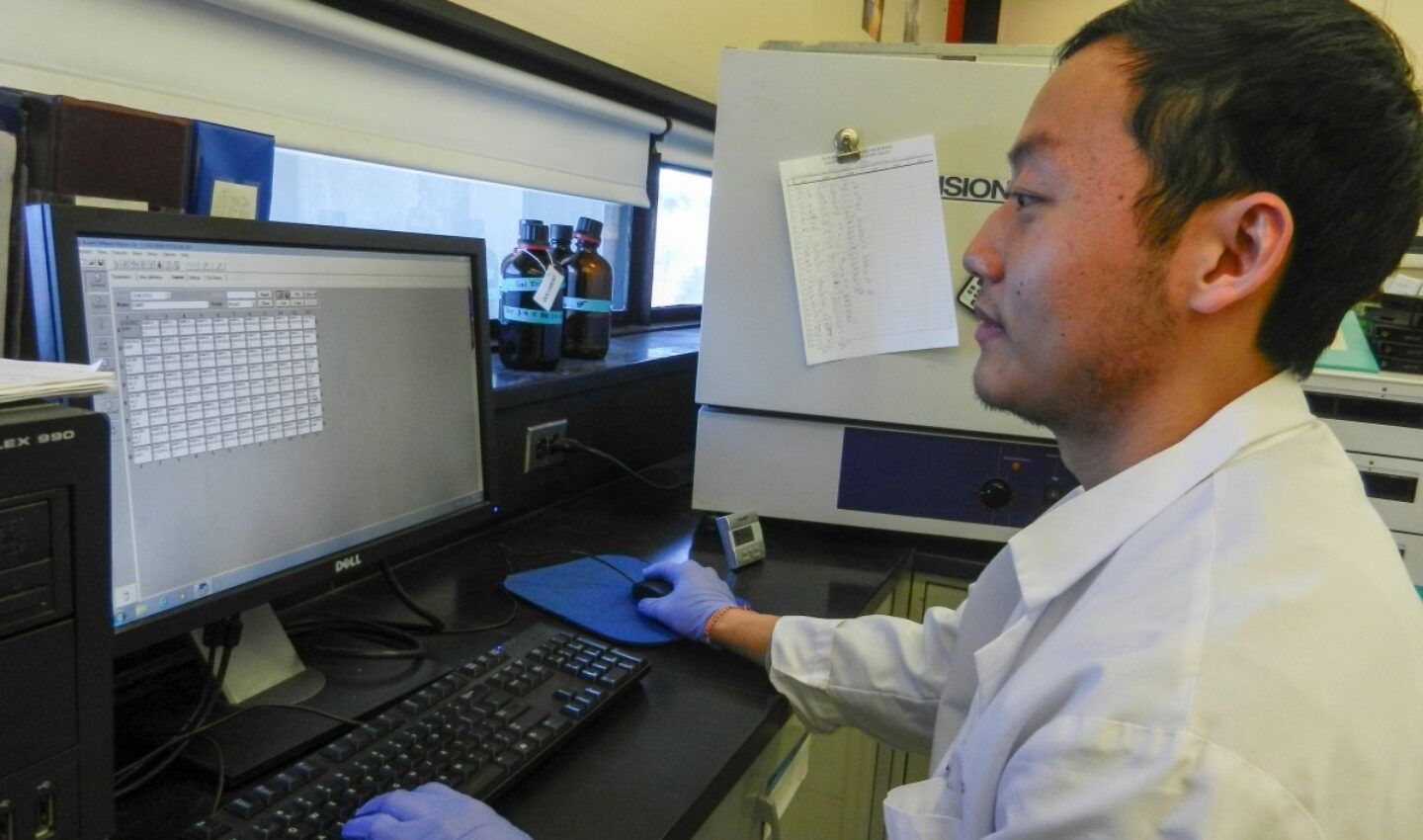

Txong Yang, another lab technician, processed Juliana’s specimen. He was near the end of his shift when the screening machine printed out the results: Juliana’s blood had more than two times the normal level of galactose. Yang immediately called his supervisor, Deborah Britton, lab analyst team lead in Metabolics, who told him to retest the blood to ensure it wasn’t a false positive. Workers hunkered down, staying into the evening hours while the blood was checked for a second time to validate the trigger for an urgent clinical call. That test also came back with elevated galactose levels.

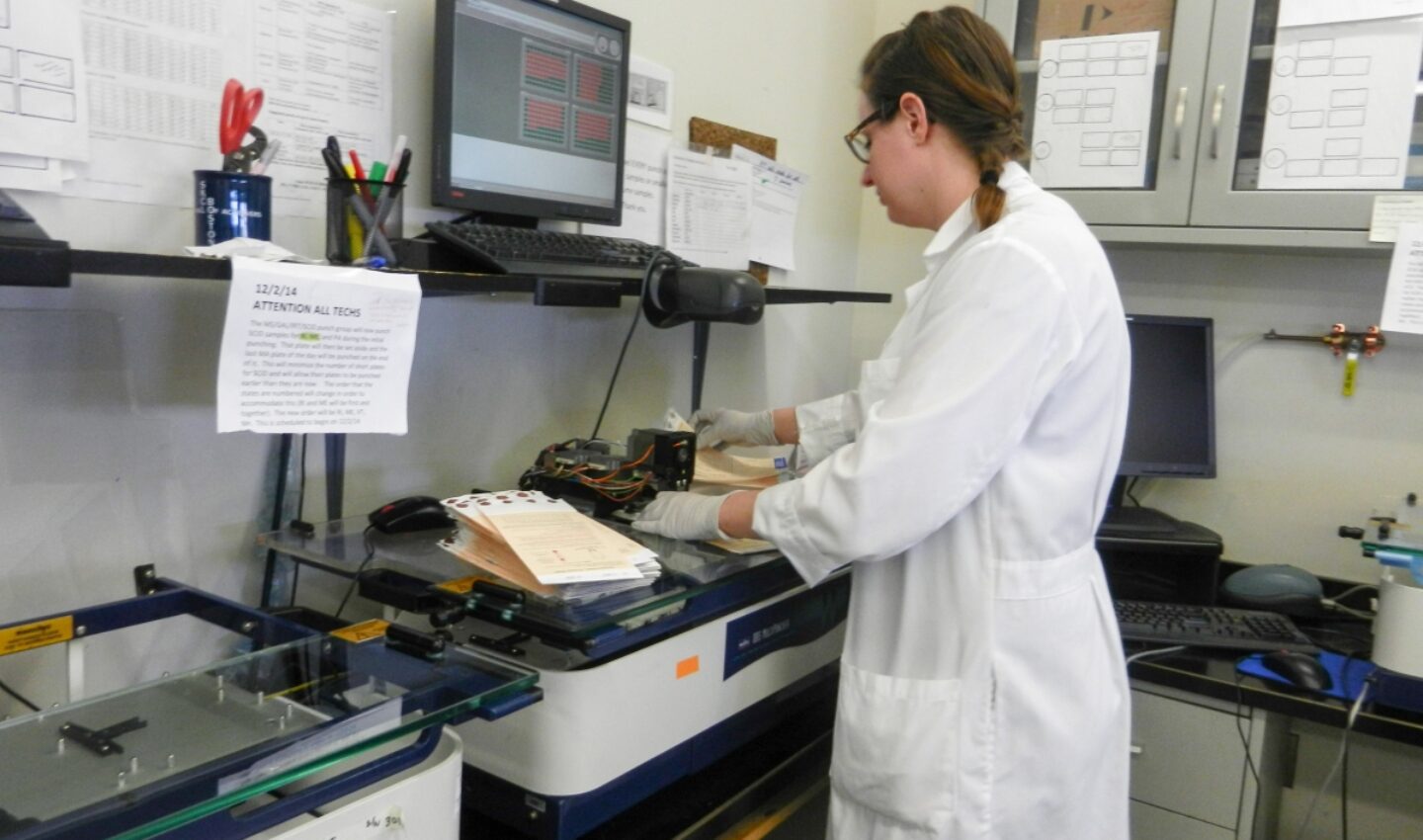

Juliana’s diet needed to be changed immediately and she needed the attention of metabolic specialists. Ensuring this happens in a timely manner is the responsibility of the follow-up team. As the screening results were developing, Clinical Data Specialist Claire Hughes did the detective work of finding Juliana’s health care provider. She advised the metabolic specialist of the pending result and called later to confirm. The work of the NENSP was completed about 9 p.m.; Juliana’s family had been advised to put her on a soy diet and seek immediate care in a NICU.

“We got it early enough and were able to get her into treatment before any serious damage was done,” Hughes said. “The outcome in this case shows that the program is a very finely tuned machine. Each person depends on the one previous to get the job done. We all work together.”

Julian’s treating physician and her parents credit the NENSP with saving her life. Juliana already had begun to show signs of jaundice and other distress when she was admitted to the NICU. Had the NENSP waited for UPS to deliver the specimens two days later, Juliana may have suffered irreversible brain and organ damage leading to death.

“It’s really wonderful that the program worked the way it should have,” Yang said. “It was definitely a week to remember for the rest of our careers.”

UMass Medical School has been operating the Massachusetts newborn screening program since 1997 in partnership with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. The lab performs metabolic and genetic screening on nearly all of the 75,000 babies born in Massachusetts annually. The program also runs screening for Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont.